Last year, banks foreclosed on almost three million homes. Five million more homeowners now owe more than their houses are worth. As a result, Americans have lost billions of dollars of personal wealth, seen their credit scores sink, and experienced serious, life-shortening stress.

And as Mark Hogan documents in his photo essay published today in Shareable.net, foreclosure is changing the face of American landscape. When I recently walked on the streets (because there were no sidewalks) of a planned community in South Florida, I saw aging, forlorn “for sale” signs; silent, empty streets; graffiti; broken windows; overgrown lawns—all the signs of a neighborhood in decline.

It’s a disaster, but it’s not an act of God. We are seeing the endgame of decades of highway building, car driving, careless lending, and TV-watching social isolation. If people, through an accumulation of personal and policy decisions, could make these now-abandoned landscapes, we the people can create new landscapes. Here are five shareable suggestions for taking advantage of the opportunities presented by the foreclosure crisis.

1. Sell foreclosed properties to local governments in a timely fashion: This idea sounds dull and vaguely socialistic, doesn’t it? But as the Living Cities report, “Communities at Risk,” argues, “By buying foreclosed properties immediately, government officials can retain the economic value and safety of neighborhood housing.” There’s another advantage: By moving the properties into the public domain, their future will become subject to democratic debate. We don’t need to simply wait for the next housing bubble: We can reconsider our entire way of life and explore alternatives… like the ones that follow.

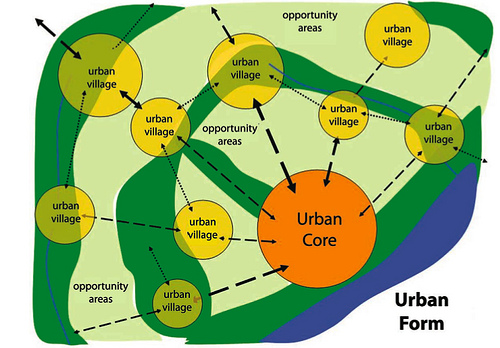

2. Shrink urban boundaries and tighten regulations: Northeastern and Midwestern inner cities have been hit hard by foreclosure, with working-class folks of color taking the brunt. But as you can see in the map above, Florida, California, Arizona, and Nevada were the states with the highest concentrations of foreclosure—a grim trend that went hand in hand with sprawl, loose development regulations, and relatively low property taxes. Since property tax revenue was restricted by measures like California's Prop 13, local governments were driven to expand the amount of taxable property in order to maintain garbage collection, schools, road repair, and so on. And indeed, within those states, the towns with the highest concentrations of foreclosure were those that spent recent decades expanding their boundaries. As Timothy Egan notes in the New York Times, the housing markets of Western cities that acted to control sprawl—Seattle, Portland, San Diego, San Francisco—have remained more or less economically stable, compared to their spread-out neighbors.

I am over-simplying things; the reality is more complicated than can be related in these brief paragraphs, and I invite readers to bring nuance to the conversation in comments. To be sure, urban developers and homeowners absolutely hate restrictive building and development codes, just as many drivers hate seatbelt and cell phone laws. I don't blame them. But the good appears to outweigh the bad, and the results speak for themselves: relatively stable housing markets, historical continuity, human diversity, smaller carbon footprints, less waste, continuing cultural and technological innovation. (Of course, every solution gives rise to new problems: As we can see in almost all of these cities, the new threat comes from gentrification, as low-income and working-class residents are priced out… but the solutions to that problem are topics for another essay.)

3. Convert abandoned houses into multi-family rental properties: Putting the houses up for rent—possibly by their foreclosed former owners—meets a number of immediate needs. But it’s logical to take it one step further and rent the house to a multiple families or individuals. My wife and I once lived in a brownstone in Boston that had been built for a nineteenth century family. But when we moved in, it was inhabited by a family, a couple, and two single people. The same is true for the San Francisco Victorian where we live today with our son: We share our house, built for one family, with our landlords and a young woman. Buildings learn to accommodate people and to evolve in response to economic, ecological, and population pressures; in this way, they can become more efficient and sustainable over time.

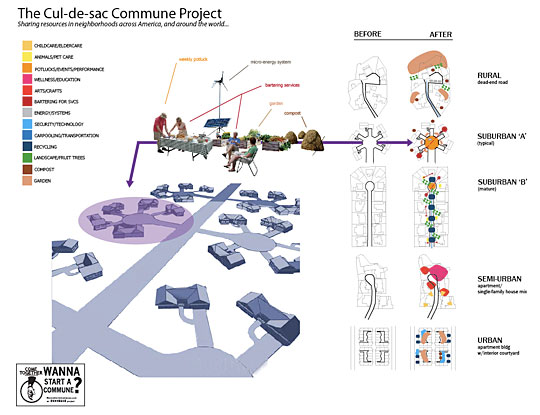

4. Convert them to cohousing: "In the past, utopian communities have often failed because people who started them have really insisted that the best way is to leave your old community, leave society, leave culture and start over,” said architect and social enterpenuer Stephanie Smith. Her company Ecoshack helped make three cul-de-sacs in California (see diagram above) more communal, trying to leverage and retrofit the resources that were already present in the neighborhood. "Every single neighborhood in America and around the world is a commune," Smith told NPR. "And every single apartment building is, and every office building is, and every single thing is built new using guidelines around sharing resources.” If we look at foreclosed cul-de-sacs through Stephanie’s communal lens, we can see new possibilities for cooperative, sustainable living.

5. Tear down the homes, upcycle the materials, and turn the abandoned lots into parks and farmland: "One of the most depressing parts of the collapse was realizing that this area had been productive farmland until the bulldozers moved in," writes Mark Hogan in his Shareable.net photo essay. "The land has now been graded, the topsoil removed, and asphalt laid—with no prospect of building houses for years." But asphalt can be torn up and recycled; land can be reclaimed for things that grow. Many of the McMansions of the past two decades were shoddily built; now in decline, they remind me of used Styrofoam cups. But they’re not actually made out of Styrofoam, and their wood, concrete, pipes, and so on, are not worthless—they can be salvaged and recycled for other uses. The land can be then be converted into parks or farmland, or put to community use—a process we can see unfolding, in messy fits and starts, in cities like Detroit. Can the same principles be applied to abandoned exurbia? That is a question worth answering.