This quarter Shareable explores the history of zoning and housing policy in the U.S. and better ways to do it. In other words, how the country I live in has shared land.

Turns out, the U.S. has done a terrible job of sharing land. In fact, we created the most wasteful land use and housing systems ever. In her book, “Redesigning the American Dream,” feminist scholar Dolores Hayden doesn’t pull any punches. “In 2000,” she says, “Americans enjoyed the largest amount of private housing space per person ever created in the history of civilization.”

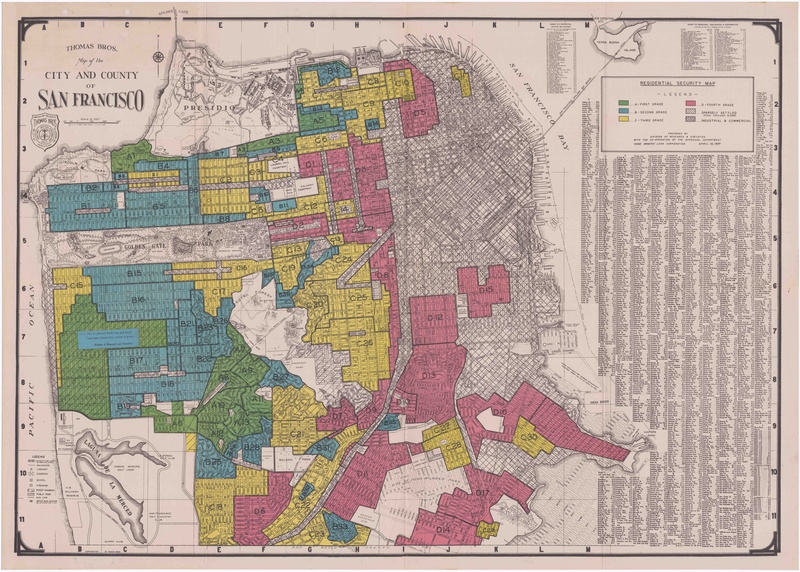

However, that space wasn’t evenly distributed. Not by a long shot. In addition to being the most wasteful system ever, it was also very racist — and it remains so even after important legal advances. All that living space is mostly enjoyed by whites. These two characteristics — wastefulness and racism — are deeply intertwined. In fact, U.S. land use and housing is wasteful because it’s racist. And it’s racism that’s at the historical root of the housing shortages plaguing job-rich U.S. cities and the massive wealth disparities between black and white Americans. Indeed, our inability to share land has led to sharing less of many other things.

Let me illustrate this by short stories of two fictional homebuyers, one black and one white, in a typical U.S. city circa 1960.

The white home buyer, Mr. Willis, wanted to move his family from the inner city to a new suburb. He found a single family home on a generous lot in the Oakdale subdivision. He was easily able to get a low-cost mortgage to purchase the home. The availability of this loan was enabled by massive federal programs designed specifically to spur homebuying by whites like him across the country. He also got better mortgage terms for being a veteran and a federal income tax deduction each year for the interest paid on the mortgage. This amounted to a very large housing subsidy to his family and others like it. In fact, buying this home was made so affordable that Mr. Willis paid less on the mortgage than he had on rent. Owning a home also allowed him to build equity, which decades later became a major portion of his family’s wealth helping to put his kids through college and buy them homes. His new neighborhood was also cleaner, quieter, more private, and better maintained than his old. It had a great school, park, and library. There was ample space between houses and much greenery. The $25 billion investment the federal government made to build the interstate highway system, the largest public works project in U.S. history, made it easy to get to and from their new home by car.

The black homebuyer, Mr. Jefferson, also wanted to move his family to Oakdale from the city. However, neither Oakdale’s developer nor any of the current residents would sell him a home even though he could afford it. The terms of the developer’s government-backed loan forbade the company to sell to anyone but whites. The deeds of current residents, all white, forbade them to sell to blacks. Mr. Jefferson couldn’t buy a suburban home, so he shopped for one in the city. He found a row house for sale in Oaklawn. He tried to get a mortgage from a local bank, but they rejected his application. Oaklawn was “redlined,” meaning the federal government wouldn’t back mortgages in black neighborhoods. The fact that he was a veteran didn’t help because black veterans were blocked from getting the VA home mortgage benefit available to whites. He resorted to his only option, a contract purchase. However, the interest rate on the contract was high and it kept him from owning the home until he paid off the note and met all the terms. Meanwhile, the lender held the deed, could evict the Jeffersons for any infringement, and the Jeffersons wouldn’t build any equity. The family could lose all they had paid in because of one missed payment. The row house was a step up, but the school was a disappointment. There was no library, few trees. Over time, the streets, park, and public services in Oaklawn deteriorated. The city neglected Oaklawn while maintaining white neighborhoods. Several of Mr. Jefferson’s friends lost their homes by missing a payment on their contract purchases. To avoid losing their home, the Jeffersons took in boarders. Others did the same. Oaklawn became overcrowded. Then a federally-funded highway project forced Mr. Jefferson’s mother to move away using eminent domain and split Oaklawn in half. Soon after, a waste incinerator opened near the Jeffersons. It fouled Oaklawn’s air and Mr. Jefferson’s daughter got asthma.

While the characters are fictional, their experiences are based on historical fact. As painstakingly detailed by Richard Rothstein in his acclaimed book, “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated American,” a separate and unequal America was created through a hodgepodge of surprisingly uncoordinated local, state, and government actions in stages over the course of a century. This system came to a peak in the post-war period.

Like the Willis’, tens of millions of white families moved to quickly expanding suburbs after World War II. These suburbs were zoned for single family houses to exclude blacks and minorities by making such homes unaffordable to most of them. This zoning code often specified minimum lot sizes, minimum house sizes, minimum parking requirements, and more, making them unnecessarily expensive. Black families that could afford a suburban home like the Jeffersons were kept out through racially restrictive deeds and other means.

Eventually, land zoned exclusively for single family houses took up the majority of residential land in most U.S. metros. For instance, Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose, Portland, Minneapolis, Charlotte, and Seattle have zoned 75 percent or more of their residential land single family. For international comparison, a recent Sightline article showed that most of Paris could fit into half of Seattle, but houses three times the population of Seattle. By 1970, more people lived in the suburbs than not, and thus a segregated, suburban society that took up vast expanses of land was realized. Today, roughly 70 percent of Americans live in single family homes and whites have the highest homeowership rate of any ethnicity by far.

Meanwhile, blacks were crowded into much smaller and chronically underinvested tracts of land in inner cities across the U.S. City planners routinely disrupted these areas by locating nuisances nearby, urban renewal projects, and running highways through them. Jessica Trounstine’s new book, “Segregation by Design: Local Politics and Inequality in America,” crunches 100 years of data to argue convincingly that local governments generated race and class segregation and that this was the basis for unfair division of nuisances and public goods. This complicated history helps explain the many disparities between black and white Americans including the fact that the median black family owns just 2 percent of the wealth of the median white family ($3,600 vs. $180,000).

While many of these racist policies and practices have been outlawed, single family zoning is still the foundation of the American Dream, standard across the U.S. This is poised to change. Many cities and states face such severe housing shortages that this bulwark of the American dream is being reconsidered. Minneapolis banned single family zoning citywide last year, a historic first. Oregon, California, several other major cities, and even political candidates are looking at residential zoning reform. It’s a miracle this trend is going nationwide in a land where NIMBY-ism has ruled, but we don’t seem prepared to take advantage of this opportunity for change yet.

Public discourse rarely reflects the racist history of U.S. housing or knowledge of more successful housing paradigms elsewhere. If unchanged, history will likely repeat itself. If market forces are left unchecked, increasing housing density and supply could make segregation and inequality worse without making housing more affordable. We could also miss the opportunity to address past systemic injustices and other urgent challenges inextricably tied to housing like climate change, pollution, traffic congestion, health, social isolation, and more.

We can’t afford to miss these opportunities to share better, yet housing discourse and solutions stay stubbornly within the paradigm that created the crisis — housing is widely viewed as a commodity, not a right and an investment in human development, sustainability, and society building.

To attempt to make a small dent in this discourse, Shareable is publishing a solutions-focused editorial series that will run through October and November. We’ll also be hosting a public event on November 6th at SPUR featuring a keynote presentation by Richard Rothstein, author of “The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America.”

I invite you to join us in this exploration, and, whether or not you live in the U.S., begin thinking about how land is used in your hometown and how that inhibits or helps you and others to share resources, and importantly, who might be left out. Apps can only do so much to help us share if the spatial organization of our communities are a barrier or unfair to begin with. We must dig deeper into, confront, and reimagine the underlying code of cities to transform them into fair, effective, and sustainable platforms for sharing resources.

##

This post is part of our Fall 2019 editorial series on land use and housing policy challenges and solutions. Download our latest FREE ebook based on this series: “How Racism Shaped the Housing Crisis & What We Can Do About It.”

Or take a look at the other articles in the series:

- Timeline of 100 years of racist housing policy that created a separate and unequal America

- How pro-density advocates in Minneapolis took on single-family zoning — and won

- Bringing equity to the forefront of urban planning

- How some cities are looking to in-law units to ease the housing crunch and build more diverse neighborhoods

- Can zoning reform undo “50 years of bad policy?”

- Segregation By Design author expects political battle between fair housing opponents and proponents

- How to ease the US housing crisis? Import strategic policy from abroad

- Cities at turning point: Will upzoning ease housing inequalities or build on zoning’s racist legacy?

- Author Richard Rothstein calls for new civil rights movement to address housing scarcity and injustice

- 8 must read books on US land use and housing policy