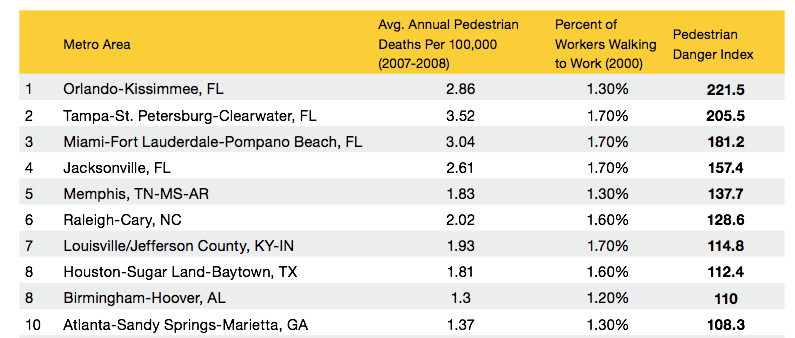

On Monday, the Surface Transportation Policy Partnership (STPP) released a new report on pedestrian safety in 360 metro areas — and they found that the top four most dangerous walking cities are in Florida. The top ten deadliest cities are all in the South.

The New York and San Francisco Bay areas ranked first and second for the absolute number of pedestrian traffic deaths — but both are also high-population, high-density areas that ranked first and second for the number of people who walk to work. More people are killed by cars because more people are out on the streets.

The New York and San Francisco Bay areas ranked first and second for the absolute number of pedestrian traffic deaths — but both are also high-population, high-density areas that ranked first and second for the number of people who walk to work. More people are killed by cars because more people are out on the streets.

"Not many people walk to work in Florida," says John Classe, an engineer and vice president of the massive PBSJ corporation, which manages construction projects around the world.

"One big reason is that it is hot for a long period of time," he says. "Weather patterns are also difficult in the summer. Plus, there is not much residential within walking distance of employment." These conditions prevail across the South, which probably explains the rankings in the STPP report.

Perhaps as a result, cities in Florida (where I lived for nine years) are not usually designed for walking or biking — and according to eRedux.com, Florida is the fourth most polluting state in the US. Each Florida resident produces 15 tons of carbon dioxide per year, compared to 11 tons in California and New York (which is nothing to brag about, by the way).

When the STPP divided pedestrian deaths per 100,000 people by the number of people walking to work in the metro area, it turned out that you are most likely to be killed on foot in the Orlando, Tampa-St. Pete, Miami, and Jacksonville areas.

Classe lives in Orlando; I met him last week at the Urban Land Institute meeting in San Francisco, introduced by our mutual friend Daniel Delisi, a planning consultant in South Florida. Classe directed the planning, design, and construction of Baldwin Park, just outside of Orlando, which has won numerous awards for its energy efficiency and walkable design. (See photo at left.) The planned community features 15 parks, more than 200 acres of lakes, and more than 50 miles of walking paths.

Classe lives in Orlando; I met him last week at the Urban Land Institute meeting in San Francisco, introduced by our mutual friend Daniel Delisi, a planning consultant in South Florida. Classe directed the planning, design, and construction of Baldwin Park, just outside of Orlando, which has won numerous awards for its energy efficiency and walkable design. (See photo at left.) The planned community features 15 parks, more than 200 acres of lakes, and more than 50 miles of walking paths.

Classe started off our conversation by describing how Baldwin Park was built along a major corridor for people commuting to downtown Orlando for work. Most neighborhoods in Florida, he and Delisi explained to me, are designed with two ways in and out (as a teenager in Ormond Beach, Florida, I actually lived in a development designed in exactly that way). As a result, residents must often drive long, roundabout distances in order to reach their strip malls and supermarkets. This is why Floridians often object to dense development — they fear the traffic.

Not so at Baldwin Park. The development is relatively dense and walkable, Classe proudly told me, and residents have 32 points of ingress and egress with their cars. This disperses the traffic and also reduces the amount of driving that residents must do — they can get in and out of the neighborhood more quickly.

But when I asked Classe about light rail (thinking that a neighborhood where everyone commutes downtown would need it), his eyebrows rose as though I had posed an odd question. "There was an effort to establish light rail in the Orlando area several years ago," he said, "but it was killed."

A week later, I described Baldwin Park’s design to a transportation engineer for the city of San Francisco–and she also looked at me strangely. "How does that help reduce the carbon footprint?" she asked. "That’s crazy. It’s better than nothing, but I wouldn’t call it ‘sustainable.’"

Those two reactions reveal the disparities in perspective between places like San Francisco and cities like Orlando.

"Maybe I have my head in the ground, maybe I spend too much time on the two coasts, but it does feel to me like this country is beginning to reshape or modulate its consumerism, and that is the first step toward sharing," Zipcar founder Robin Chase told me in our Shareable Q&A. I share Chase’s hopes, but conversations with folks like Classe and Delisi remind us that word of the sharing revolution hasn’t yet reached places like North Central Florida. They judge their efforts toward sustainability by a different standard than does a transportation engineer in San Francisco.

Delisi and I met as students working on environmental issues in Boston. He’s taken those values with him as a planner to Florida, hoping to make a difference, but over the years he’s had to content himself with small victories. "Success for me in South Florida is building a strip mall that people can walk to," he told me. But why should those people walk, the STPP report suggests, if they are so likely to be hit by cars?

Florida doesn’t necessarily lack money for pedestrian and bike safety; it lacks the political and cultural will. It’s not alone among the states.

Florida doesn’t necessarily lack money for pedestrian and bike safety; it lacks the political and cultural will. It’s not alone among the states.

Since 1992, the Transportation Enhancements (TE) program has set aside 10 percent of each state’s federal aid for green transport. But the authors of the STPP report (fittingly titled "Dangerous by Design") found that most states have spent only 80 percent of the nearly $9.4 billion made available through the TE program, and only 35 percent of the Safe Routes to Schools program since 2005.

What’s the solution?

Developments like Baldwin Park may not be perfect, but they suggest that Florida can take steps in a more sustainable direction. State and federal policy changes would help: The report recommends requiring that federal safety money be spent in an amount proportional to the risk facing pedestrians and that we adopt a national "complete streets" policy that would require cities and counties to accommodate all road users. But in the end, that’s not enough.

"There still is a long way to go to repair the damage done to communities in the past, even as we begin to shift policies and design philosophy to build streets that are safer for pedestrians and motorists alike," says the STPP.

However, there are a growing number of excellent models to build on and thousands of communities eager to move forward. The forthcoming rewrite of the nation’s transportation policy presents a once-in-a-generation opportunity to create safer streets that will be critical to keeping our neighborhoods livable, our population more fit and our nation less dependent on foreign oil.